What it takes to get the food to where it needs to go: Reflections on my 27 years with the UN and the World Food Programme

My career with the UN started in 1978, with the World Food Programme, in Rome. I had just arrived from my home country of Myanmar.

My first big challenge came in January 1979, when I was asked to travel to Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania to try and salvage some six thousand tons of assorted food, mostly from the U.S. and the EU, that was stuck in the port, for varying periods of time, some over many months, on their way to Bujumbura in Burundi.

The WFP Country Director and our agent, AMI, the Belgian international freight forwarders, had both informed us that the goods could not be sent to Burundi due to a number of factors, primarily stemming from the on-going war in the West Lake Region between Idi Amin’s Uganda on one side and Kenya and Tanzania on the other.

My task was to see what can still be salvaged and sold as distressed goods and the rest to be disposed-off locally in the best manner possible.

The fifteen years of experience in shipping, port, customs and cargo operations I had under my belt at the time did not prepare me for the shock that awaited me in the port of Dar that day.

Such was the complete and utter chaos! The Burundi/Kigom transit facility at Dar that normally has a capacity of about 3,000 tons had over 17,000 tons of assorted Burundi-bound goods, most of which had overflowed into the regular Tanzania port area, stymying operations of the port almost to a stand-still.

I determined that the only viable option was to take all the food consignments out of the port to a large gated storage facility about 10 miles away, the Ubungo facility. There, the goods could be separated, good from bad, fumigated and re-conditioned.

Moreover, gentle but firm arm-twisting of the concerned entities like the Burundi Ambassador, the USAID Director in Dar, the Tanzanian Railways, AMI who also represented the US NGOs also and to seek the willing collaboration of the Tanzanian Port, Customs and Railway Authorities made it all happen.

WFP headquarters very quickly sent the US $20,000 I had asked for to meet the expenses for this operation. Samples of all individual consignments were sent via the UK Embassy pouch, to Tropical Stored Products Centre (TSPC} in the UK for quality and condition testing. Goods no longer fit for human consumption were donated to the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) assisted feed farm outside Dar. Quite miraculously, I and my capable shipping assistant Franco Mascarino, after working extremely long hours, often foregoing meals, were able to dispatch dedicated block-trains direct from Ubungo to Kigoma, within three to four weeks.

All except a consignment of about 700 tons of bagged wheat flour which was fast running out of shelf-life and needed to be consumed fast, was put on road trucks and sent to a UNHCR-run refugee center in what was then called Zaire.

This mission’s achievement was simple enough: over 6,000 tons of food, already classified as lost and given up for good, was saved and put back at the disposal of the, the school-children of Burundi, for whom it was originally intended. The report of this Mission was very warmly received in Rome, including by the then Executive Director of WFP, the Canadian, Gerry Vogel, who remarked that what was accomplished was a “Mission Impossible.”

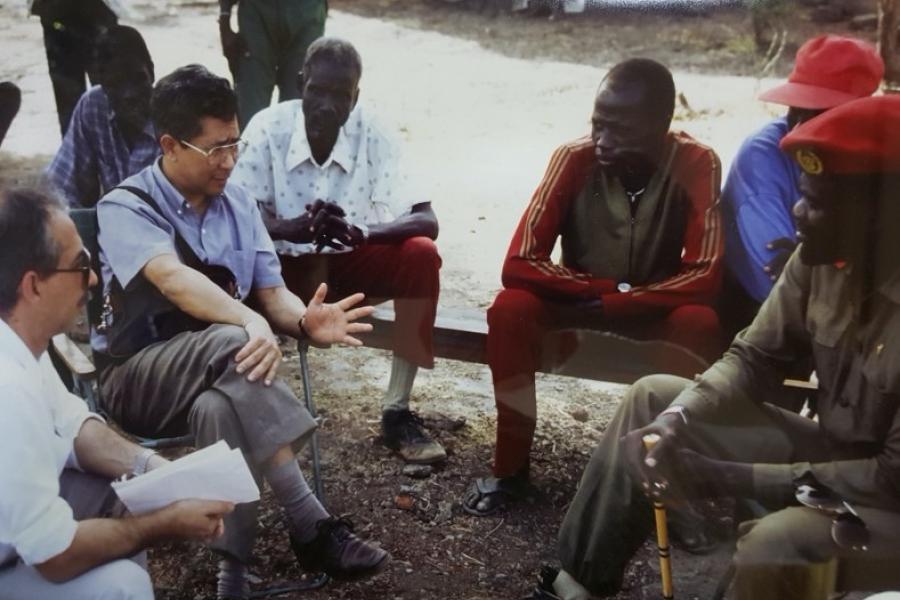

The World Food Program is known simply for distributing food to those who need it. Behind the scenes, the work of WFP is complex. It entails complicated logistics, communicating across languages and cultures, negotiations among parties with competing interests, unpredictable natural and political events, finding the best solution possible under difficult circumstances and time pressure.

It is the dedication of the WFP staff worldwide that have earned the organization the Nobel Peace Prize. I salute colleagues at the organization, and I hope that this prize inspires many more people to get involved in the UN’s work.

This first challenge of my career—and many others—shows that one does not necessarily need to be at a senior-level position in the UN to make a difference! I was a rookie who had yet to complete my probationary requirements when I undertook the mission to Dar. Hard work and a judicious application of one’s experience, knowledge, and good sense can prove to make the difference.

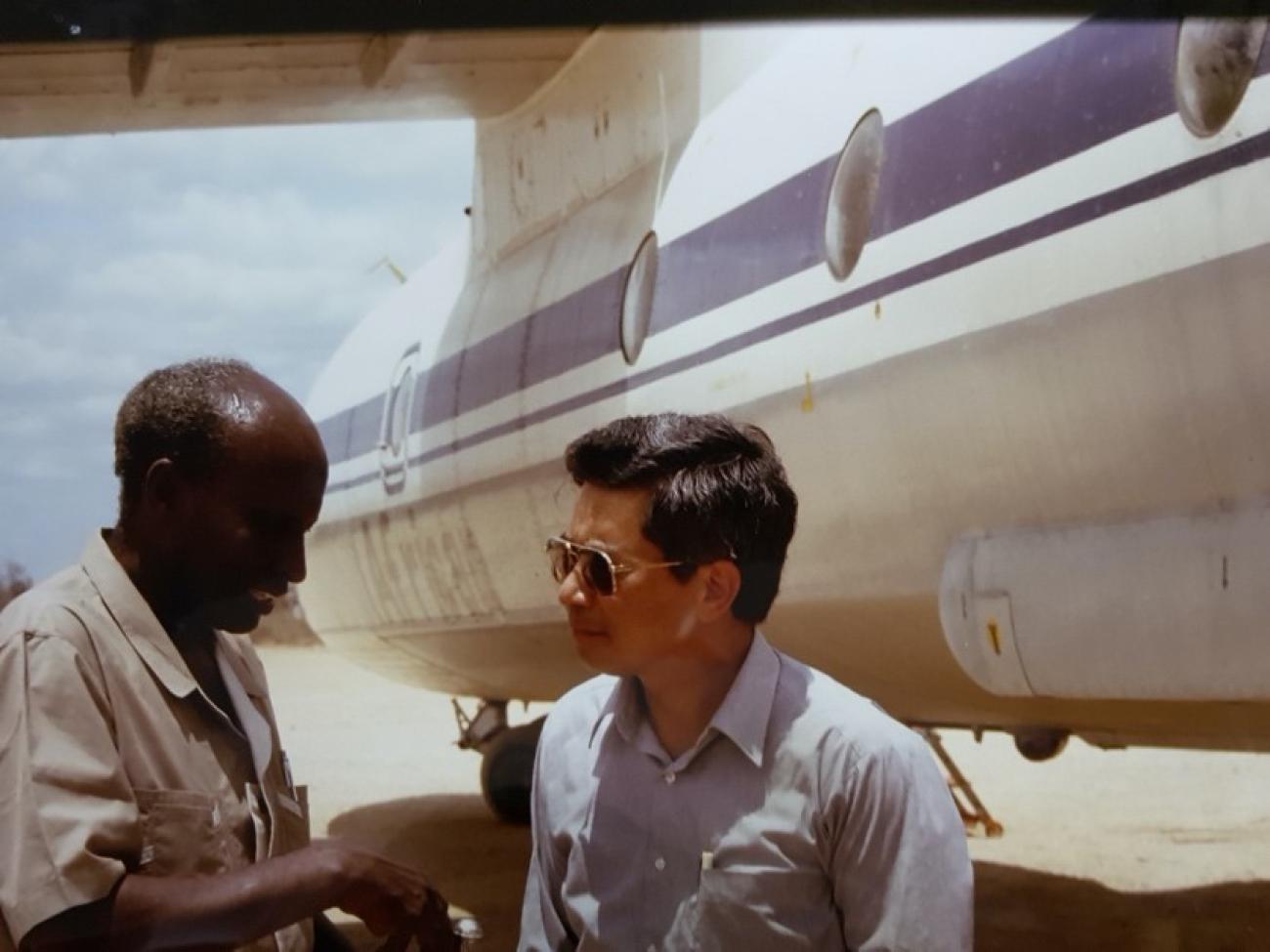

The author is Mr. Tun Myat, a former career UN veteran of 27 years, who started at WFP Headquarters in Rome, Italy in 1978. He became he became Chief of Staff to the then Executive Director of WFP in 1988, Director of the Logistics Division in 1991, and Director of the Resources and External Relations Division in 1997. In April 2000 he was appointed by the then UN Secretary-General as UN Humanitarian Coordinator in Iraq and was later transferred to UN Headquarters as UN Security Coordinator in July 2002. He retired in September 2004 at age 62. He now lives in retirement in Yangon, Myanmar with his wife of 55 years.

Written by